Wexford, Ireland. Ronald Reagan’s origins are even more humble than Abraham Lincoln’s log cabin.

His great-grandfather, Michael O’Regan, was born in a hut of mud and slats in farmland called Doolis near the village of Ballyporeen, County Tipperary, in 1829.

The O’Regans, like most of Ireland’s rural poor, lived on potatoes. When a fungus (phytophthora infestans) infected the potato crop in 1845, causing a famine, the teenaged Michael fled to London with other folks from Tipperary. Among them was a young lass, Catherine Mulcahy, whom he married in 1852 after Anglicizing his name to Reagan.

They had a son, John, in 1854, and emigrated to America, settling in Fulton, Illinois, by 1860. John’s son, Jack, was born in Fulton in 1883. Jack’s son, Ronald Wilson Reagan, was born in nearby Tampico in 1911.

Seventy-three years later, in June of 1984, Ronald Reagan came to Ballyporeen as President of the United States. In his speech to the townspeople in the village square, he said, “I can’t think of a place on the planet I would rather claim as my roots more than Ballyporeen, County Tipperary.”

A friend of mine was there as a member of Reagan’s staff. After the speech, the President commented to him, “I really am proud to be from here.” With a wink, he explained: “You see, I’m from Beyond the Pale.”

My son Jackson and I are here in Ireland to track down his own Irish roots. His mother’s great-grandparents emigrated to America from somewhere in Ireland in the 1890s. It turned out they were from Beyond the Pale too.

The history of Ireland is long, and too often dark and grim. It’s been inhabited for 9,000 years, first by Stone Age folks whose megalith (“giant stone”) monuments and graves can still be seen by the hundreds, scattered across the island today – such as “The Hole of Sorrows” in County Clare.

By 2500 BC, they had entered Ireland’s Bronze Age, skillfully casting axes, daggers, and other weapons, and producing spectacular ornaments of beaten gold. The Iron Age began around 500 BC, with a series of migrations from Europe by tribes of Celts (from Herodotus’ (484-425 BC) name for them, Keltoi).

The last Celtic tribe to come called themselves Gaels, from their homeland in Gallaeci, modern-day Galicia in northwestern Spain. They established a number of kingdoms throughout the island, which they called Eire, after the earth-goddess they worshipped, Eriu.

Experience the Insider community that takes your international lifestyle to the next level. Download your FREE guide

"18 Steps to Implementing Your Plan B" instantly!

Thus, the name of the Irish language and culture, Gaelic, and Ireland’s name, the Land of Eire.

Although the Romans, starting with Julius Caesar in 54 BC, invaded and colonized England, they left Ireland alone, calling it Hibernia. This, after Pytheas of Masalia (today Marseille), a Greek merchant-explorer who circumnavigated the British Isles in 325 BC, called it Ivernia, adapted from Eire.

The gradual replacement of the Celtic Druid religion with Christianity traditionally begins with the arrival of St. Patrick as a Catholic missionary in 432 AD. The patron saint of Ireland, his death day of March 17, 493, is celebrated by all those who want to be Irish.

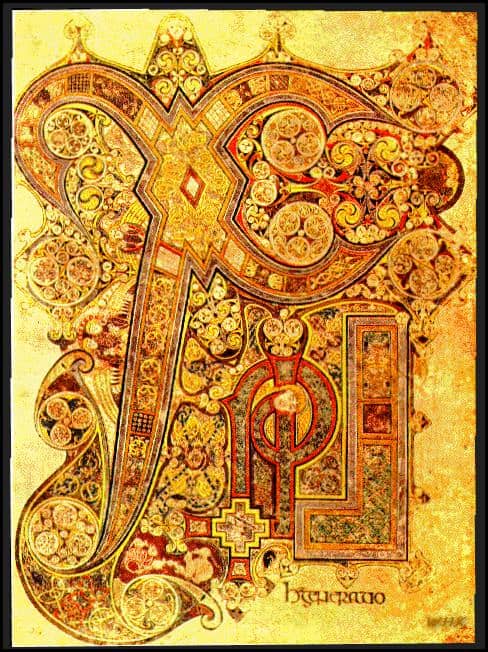

By 600, monasteries had been built all over Ireland. The monks studied the Scriptures in Latin and produced magnificently illustrated manuscripts, such as the astounding Book of Kells at the Abbey of Kells, County Meath, in 800. It is Medieval Europe’s greatest treasure and one of the most astonishing works of art in human history. Here is the Chi-Rho Monogram page:

Most all Irish men were either monks, farmers, or warriors for the local king, whose favorite pastime (as it had been for centuries) was cattle-raiding and pillaging neighbor kingdoms.

Then in 832, the Vikings arrived and pillaged the entire island. By 870, the Vikings decided they liked the place enough to stop destroying and start building towns. They proceeded to found several of Ireland’s largest cities, Dublin, Wexford, Limerick, and Cork.

Near Limerick in the 960s, a young Gaelic prince named Brian Boru (941-1016) organized a guerrilla army to fight the Vikings. With each victory, his army grew until he had kicked the Vikings out of Ireland.

By 1002, he reigned over all Ireland except Ulster in the north. It took him 10 more years to gain control of Ulster, whereupon he was proclaimed Ard Ri, the first – and last – High King of all Ireland.

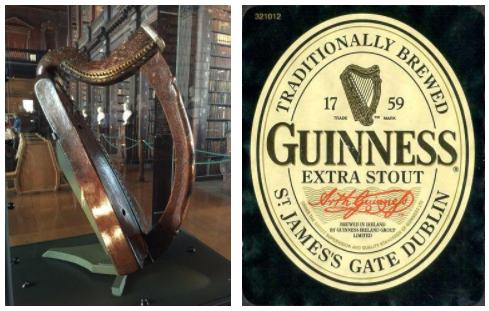

Today, the Clan of O’Brien claims descent from Boru, while Brian Boru’s Harp remains the symbol of Ireland. Look for the harp on the label of a bottle of Guinness.

After Boru, the island quickly broke apart into the usual warring kingdoms. Across the Irish Sea, England was about to change forever with the invasion of William of Normandy in 1066. The French-speaking Normans seized all of Britain, with a number of Norman knights taking control of Cambria, later known as Wales.

These Cambro-Normans decided Wales wasn’t enough for them, and they launched an invasion of Ireland in 1169 led by Sir Richard “Strongbow” de Clare. Landing at Ballyteige Bay south of Wexford, they quickly took Waterford and the entire east coast to Dublin.

One of the knights was Sir Walter de Whitty, who built Ballyteige Castle overlooking the bay. It still stands today and was the ancestral home of the Whitty family until 1649:

Here is where Jackson’s Irish roots began. His great-great grandfather was a Whitty.

In 1171, King Henry II of England (1133-1189, husband to Eleanor of Aquitane, the most extraordinary woman of the Middle Ages, and father to Richard the Lion Heart) sailed to Waterford to parcel out the Irish territories conquered in his name. Strongbow got the largest, while Henry kept Dublin under his personal royal control.

Pope Adrian IV had just issued a Papal Bull anointing Henry as “Lord of Ireland.” Dublin and the territory around it for a radius of about 20 miles was therefore named the Lordship of Ireland.

The Cambro-Normans soon became known as Hiberno-Normans (Hibernian or Irish Normans) as they assimilated with the Gaels and lost their loyalty to the English Crown. By the 1300s, a ditch had to be built around the Lordship of Ireland to protect it from Irish raiders.

The ditch was fortified with pointed stakes, or pales, from the Latin palus (stake). The words impale and palisade have the same root. Thus, the Lordship of Ireland became known to the English residents within it as the Pale. Inside the Pale, it was safe and civilized. Outside, or Beyond the Pale, it was neither.

By 1500, the British Crown had lost control of the Pale itself. The War of the Roses (1455-1485) between the Houses of York and Lancaster for the throne had torn England apart. The Hiberno-Norman Earl of Kildare, Gerald FitzGerald (1456-1513; “Fitz” is a Hiberno-Norman prefix) had taken over the Pale, and there was nothing King Henry VII could do about it.

His son Henry VIII (1491-1547) couldn’t do much about it either. He tried everything from force to bribes to “politic drifts and amiable persuasions,” and nothing worked. The Irish, Gaelic together with Norman, stayed outside English jurisdiction, maintaining their own language, social system, customs, and laws.

Finally, in 1541, Henry declared the Lordship of Ireland to be the Kingdom of Ireland, himself the King of Ireland in addition to the King of England, and said to hell with the place. He died six years later.

So the Irish remained free, but at a cost. The Renaissance had passed Ireland completely by, so its culture remained firmly medieval, still stuck in the feudal Middle Ages.

The Reformation passed Ireland by as well. While the English, after Henry broke with Rome in 1536, became increasingly Protestant (along with the Welsh and the Scots), the Irish remained passionately Catholic.

We may call Henry’s daughter, Elizabeth (1533-1603), the “Great,” but she is despised by the Irish. She was a Protestant, assuming the throne in 1558. In 1570, Pope Pius V issued a Bull absolving the people of Ireland from any allegiance to England and its Protestant Queen.

She responded with ferocity, attempting to subjugate the Irish with massacres and brutality. This culminated in the Nine Years’ War, 1594-1603.

The most resolutely Gaelic and Catholic province of Ireland was Ulster in the north. The rebellion led by Hugh O’Neill was crushed by an English scorched-earth policy, resulting in tens of thousands of Irish starving to death. Yet Ulster celebrated shortly after the war’s end when James I (1566-1625), grandson of Henry VII, succeeded childless Elizabeth. James was a Catholic.

James proceeded to screw the Catholic Irish more than any Protestant English King.

Ever since Henry VIII, the British had tried to establish “Plantations” in Ireland, seizing the lands of rebellious Irish chieftains and giving it to English settlers, with most efforts literally ending in bloody disasters. James’s Plantation of Ulster was different.

First, he confiscated three-quarters of all the land in Ulster, and forced by sword-point all the Irish inhabitants to relocate in the remaining quarter. Then he invited thousands of Protestant Scots to take over and settle in the seized and de-populated lands. The Protestant Church of Ireland was awarded all lands and churches owned by the Catholic Church in Ulster.

It is from these Scot immigrants in the early 1600s that today’s Protestant population of Ulster, or “Northern Ireland,” descend.

This land-confiscation Plantation policy was expanded through Ireland by James’s son, Charles I (1600-1649, England’s shortest King at 5’4″) when he gained the throne in 1625. The Irish finally exploded in 1641.

The Rebellion of 1641 saw thousands of Protestant settlers murdered and the collapse of the British colonial government in the Pale. An Irish government was formed called the Catholic Confederacy, which issued a Declaration of Independence from England, and was formally recognized as the legal government of Ireland by France, Spain, and the Vatican.

Yet Charles’s autocracy (he was convinced of the Divine Right of Kings to absolute obedience) was causing the English Parliament to rebel against him as well. The resulting English Civil War between the Parliamentarians and Royalists ended in the beheading of Charles for treason in 1649, and the seizure of power by a fascist monster named Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658).

Cromwell’s evil was driven by an Ayatollah Khomeini-like religious fanaticism and hate. His New Model Army invaded Ireland in 1649, and on Cromwell’s orders, butchered thousands of Catholics in cold blood at Drogheda (north of Dublin), including Catholic priests in St. Peter’s Church. The survivors were shipped to the West Indies and sold as slaves.

The barbarity was repeated at Wexford, where over 2,000 men, women, and children were slaughtered. Luckily, Cromwell and his army had to then retire to winter quarters where many of his soldiers died of dysentery and typhoid.

Unable to complete his conquest due to endless guerrilla attacks by Irish calling themselves tories (from the Gaelic toraidhe, pursued man – thus Tory evolved from outlaw to British political conservative), he began systematically destroying Ireland’s food supplies.

The massive famine caused the Irish to surrender in 1653. By that time, 30% of Ireland’s entire population had died or had been sold into slavery or exiled.

Cromwell’s “Commonwealth” dictatorship confiscated all land owned by Catholics in the entire island. Catholics were reduced to powerless poverty and rule by a Protestant aristocracy known as the Protestant Ascendancy had begun.

When Cromwell mercifully died in 1658, the Restoration of the British Monarchy ensued with Charles II (Charles I’s son), who oversaw Ireland with a “live and let live” attitude.

Trouble started again when Charles died in 1685, and his brother James, Duke of York (for whom Charles renamed New Amsterdam to New York in America when he captured it from the Dutch in 1665) ascended as James II.

The Irish celebrated, for James was a fervent Catholic. But the Protestant British did not. James tried to appease them by letting his daughter, Mary, marry a Protestant, William, Prince of Orange, in the Netherlands. This was a little spooky because William’s mother was James’s sister. William and Mary were first cousins.

It did nothing to assuage the Protestants, who plotted to overthrow James in a coup d’etat and replace him with William and Mary as Joint Sovereigns. They succeeded in what is known as the Glorious Revolution of 1688.

James II fled to Ireland. The Catholics had regained enough influence to get the Irish Parliament to declare that James remained King, and to pass, at James’ urging, an Act for Liberty of Conscience which granted religious freedom to all Catholics and Protestants in Ireland.

William promptly led an army to Ireland and trounced James at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. He then proceeded to enact a series of Draconian punishments upon the Irish Catholics, known as the Penal Laws. For this, his name is enshrined in Irish memory as “William the Turd.” (To certain historians, he is also known as William the Bisexual.)

Almost all Catholic land was again confiscated, almost all political rights denied. Catholic schools were banned. Catholics couldn’t even own a horse worth more than five pounds.

The Protestant Ascendancy ruled Ireland for the entire 18th century, with a stability that brought both peace and prosperity. Ireland finally emerged out of the Middle Ages. The Penal Laws faded away. Protestants began to feel far more Irish than English. Capitalist trade created wealth, with rich merchants building grandiose Rococo mansions.

The middle class grew, as did literacy, art, music, and literature. Jonathan Swift (born in Dublin, educated there at Trinity College) wrote Gulliver’s Travels in 1726. George Berkeley from County Kilkenny became one of the most well-known philosophers in the world (the University of California at Berkeley is named after him).

Dublin became a boom town, a city, as one historian described it, “full of exciting ideas, high living, much business, much pleasure, rakes, bucks, and expensive whores.” By the 1780s, Dublin was second in importance only to London in the British Isles.

Yet the Ascendancy still owned most of the land and had all the political power. The American and French Revolutions inspired the Catholics to increasingly demand democratic rights. A rebellion in 1798 frightened the Protestant aristocracy enough to relinquish power and support the British Parliament’s Act of Union, creating the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801.

The Catholics (who formed 80% of the population) continued to press. A formidably intelligent champion emerged, Daniel O’Connell (1775-1847), who almost singlehandedly persuaded the British Parliament to pass the Catholic Emancipation Act in 1829, repealing the Penal Laws and other anti-Catholic legislation.

The Irish celebrated. Then came the Potato Famine. From 1794 to 1845, Ireland’s population almost doubled to over 8 million. By 1851, over 1½ million had died, and another 1½ million emigrated, many to America.

The Catholic survivors continued to press. Ireland began to be divided between Unionists (who called themselves Orangemen after William of Orange) centered in Protestant Ulster demanding no change in the 1801 Union, and Republicans, Catholics who wanted “Home Rule” – an autonomous (ideally independent) Irish Republic.

By 1914, an outbreak of civil war between armed militias of Unionists and Republicans seemed certain, as Parliament was poised to pass Home Rule. Then World War I intervened.

This frustrated a group of Republicans who staged a week-long rebellion in Dublin in 1916 called the Easter Rising. The violence was unpopular, but the British reaction to it more so, especially when the Rising leaders were executed. Then came the Brits’ biggest blunder.

To raise soldiers to fight the Germans, they announced they would now conscript Irish men into the British Army. Catholic Ireland exploded. It formed Volunteers into an Irish Republican Army (IRA) led by Michael Collins, who savagely fought British Army “Black and Tan” units that indulged in massive looting and civilian torture. By 1920, Collins and the IRA were winning.

By 1921, British Prime Minister Lloyd George was negotiating a treaty with Michael Collins. They signed an Anglo-Irish Treaty to create an Irish Free State with “dominion” status within the British Empire. Two provisos infuriated Republican purists: that six Ulster counties (“Northern Ireland”) could opt out of the Treaty – which they immediately did – and that Irish Parliamentarians had to take an Oath of Allegiance to the British Crown.

So a civil war erupted between pro- and anti-treaty forces within the IRA. Collins had to suppress the revolt, and was succeeding when, on August 22, 1922, near Cork, he was assassinated by anti-treaty IRA men. He was 31 years old. The whole country went into a state of shock. To this day, Collins is revered as Ireland’s greatest patriot.

The war slacked off and the Free State floundered until Eamon de Valera (1882-1975), long-time IRA leader and founder of the Fianna Fail (Soldiers of Destiny) party, was elected Prime Minister in 1932. With a couple of interruptions, he remained Ireland’s Prime Minister until 1959.

De Valera immediately repealed the Oath of Allegiance to the British Crown from Irish law. By 1936, he had the IRA banned as an illegal criminal organization. By 1937, he had a new Constitution adopted, making Ireland completely sovereign from Britain and changing the country’s name to the Republic of Eire.

At last, Ireland was free after 800 years of British subjection.

Nonetheless, it was one of Europe’s poorest countries and remained so, slowly improving under de Valera, regressing under incompetent politicians like Jack Lynch in the 70s and corrupt ones like Charles Haughey in the 80s.

Finally, Ireland figured out that low-tax, free-market entrepreneurial capitalism was the key to prosperity. The man who primarily figured it out was Charlie McCreevy, Ireland’s Minister of Finance (1997-2004). The result of his policies was The Celtic Tiger.

That’s what Ireland’s now-booming economy became known as, with Ireland now one of the wealthiest countries in Europe, and ranked by the World Bank as having the 6th highest GDP per capita in the world. It’s a thrilling success story.

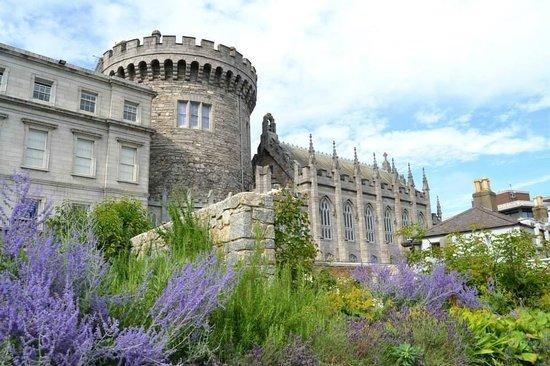

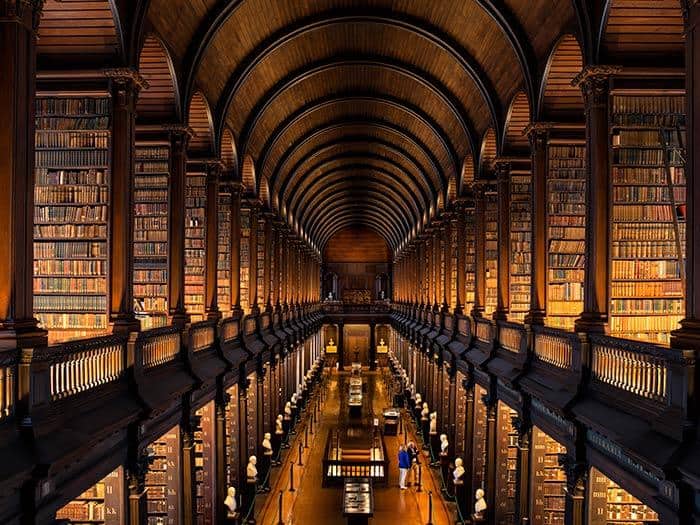

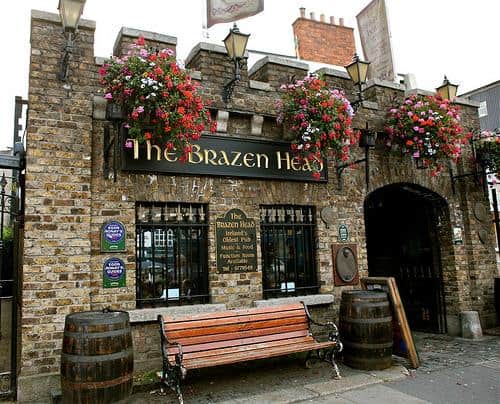

Dublin is one of the hottest destinations in Europe for travelers. And no wonder, with Dublin Castle, Christ Church Cathedral, Trinity College’s Long Room Library (where the Book of Kells and Boru’s Harp are displayed), and the Brazen Head Pub (Ireland’s oldest, established 1198).

Dublin Castle

Christ Church Cathedral

The Long Room

Brazen Head Pub

But that’s just the start. There’s The Wonderful Barn in County Kildare – a huge stone corkscrew tower built in 1743 to house grain during famine – it’s like no barn you’ve ever seen.

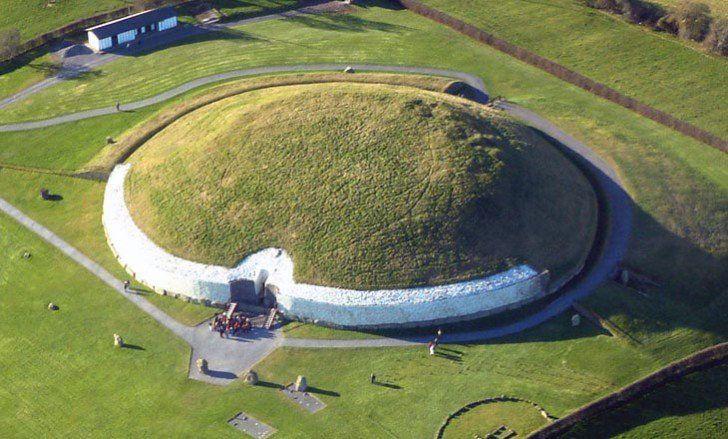

Or Newgrange in County Meath. Here is the magnificent Megalithic Passage Temple built over 5,000 years ago (3200 BC) in worship of the Ancient Irish Sun-god Dragha. Together with the massive temples of Knowth and Dowth, it comprises the Brú na Bóinne World Heritage Site.

The Wonderful Barn

Newgrange Megalithic Passage Temple

In County Mayo there’s the small village of Cong – where John Wayne’s iconic movie The Quiet Man was filmed in 1951. Directed by John Ford, co-starring Maureen O’Hara, it is one of the most beloved films of all time. Many of the locations are still there, from the bridge Barry Fitzgerald and John Wayne crossed, to Pat Cohan’s pub where Wayne’s climactic fight with Victor McLagen ends.

“Quiet Man” Bridge

Cohan’s Pub in Cong

Speaking of movies, there’s the hideout of Luke Skywalker – who, as the latest Star Wars movie reveals, resides on the extraordinary island of Skellig Michael off the coast. It is a World Heritage Site as a nature sanctuary and as the earliest monastic complex of the first Irish Christians in the 600s.

Of course there are castles, such as Ireland’s iconic medieval masterpiece, The Rock of Cashel, built on the site where St. Patrick converted the King of Munster to Christianity in the mid-400s. And Kilkenny Castle at Ireland’s medieval capital, with its Medieval Mile.

The Rock of Cashel

Kilkenny Castle

Jackson and I, however, had to drive quite a bit to find his Whitty ancestors’ birthplace. Cromwell’s soldiers seized Ballyteige Castle in 1649 together with all Whitty lands, and the Whittys dispersed.

Thanks to the research of a distant relative, Maura Whitty in Wexford, we learned that my wife’s great-grandfather (thus, Jackson’s great-great), James Patrick Whitty, was born in 1869 in a farmhouse on land called Kyle in the remote Wicklow mountains. That’s where the family fled to after Cromwell.

The farmhouse is gone and there’s only fields and countryside now – but what gorgeous country it is. They call Ireland the “Emerald Isle” for good reason.

It’s astonishing that such a breathtakingly beautiful place as Ireland could be the scene of so many centuries of oppression and tragedy. Perhaps even more astonishing is how the Irish people are triumphing over their past.

Kyle is very much like Doolis, the farmland of Michael O’Regan. Both are far Beyond the Pale. But as Ronald Reagan understood, it’s often a good and useful thing to be beyond the borders of “acceptable” society. In that direction lies freedom.

For some great reading, here are a few articles I know you’ll enjoy!

Misunderstood: Common Misconceptions About Countries that Don’t Seem to Disappear

Living Warm and Dry in Cosy Southeast Ireland

©2019 Jack Wheeler – republished with permission

Like Our Articles?

Then make sure to check out our Bookstore... we have titles packed full of premium offshore intel. Instant Download - Print off for your private library before the government demands we take these down!