The Pamir Knot

All photos by Jack Wheeler

The Pamir Knot of Eastern Tajikistan, the Wakhan of Afghanistan, and Northern Pakistan.

The Pamir Knot of Eastern Tajikistan, the Wakhan of Afghanistan, and Northern Pakistan.

Kashgar, Chinese Turkestan. About 55 million years ago, the giant subcontinent of India, which had been drifting north for tens of millions of years after breaking off from the supercontinent of Gondwanaland, began crashing into the Eurasian landmass at a speed of 8 inches a year.

It hit not flat-on but at an angle, with the huge projecting tip of the northwest corner of India slamming into Asia first. As it bulldozed underneath Asia (a process called subduction), an Asian inland ocean called the Sea of Tethys (named after a Greek sea goddess) was tilted up and drained off, becoming the Tibetan Plateau.

The edge of Asia buckled like crinkled paper, creating the world’s greatest mountain ranges, including the Himalayas. Mount Everest, now at 29,028 feet, was once the bottom of the Tethys Sea, and because India continues to drive under Asia at over a tenth of an inch a year, it will reach over 30,000 feet in less than two hundred thousand years.

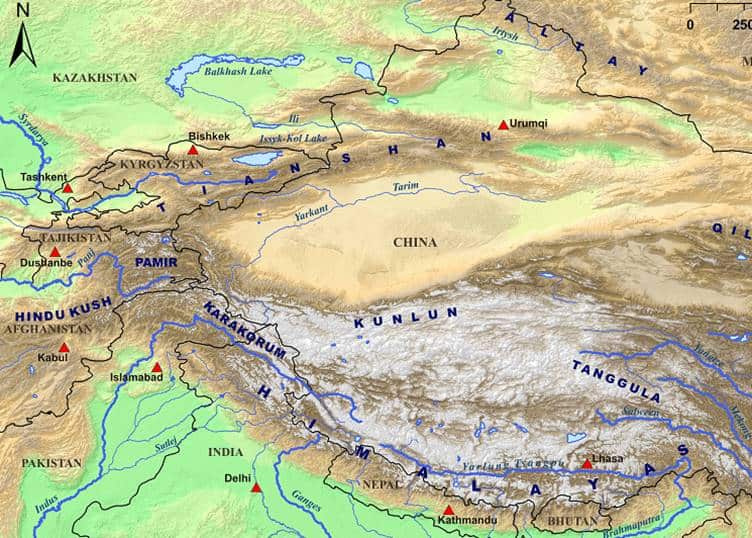

The Himalayas were but one mountain range buckled up by the India-Asia collision. From that projecting tip of the collision, enormous mountain ranges radiated out: the Tien Shan to the north, the Hindu Kush to the south, the Kun Lun to the east, and the Karakoram-Himalaya to the southeast.

The center of this radiation is the tortured jumble of gigantic mountains you see in the sat photo above, the Pamirs over 20,000 feet high amidst a plateau of over 14,000 feet known since ancient times as “The Roof of the World.” The welter of mountain ranges comprising this jumble has been called since the days of Marco Polo (1254-1324) “The Pamir Knot.” Polo crossed it in 1272. I just finished crossing it.

The center of this radiation is the tortured jumble of gigantic mountains you see in the sat photo above, the Pamirs over 20,000 feet high amidst a plateau of over 14,000 feet known since ancient times as “The Roof of the World.” The welter of mountain ranges comprising this jumble has been called since the days of Marco Polo (1254-1324) “The Pamir Knot.” Polo crossed it in 1272. I just finished crossing it.

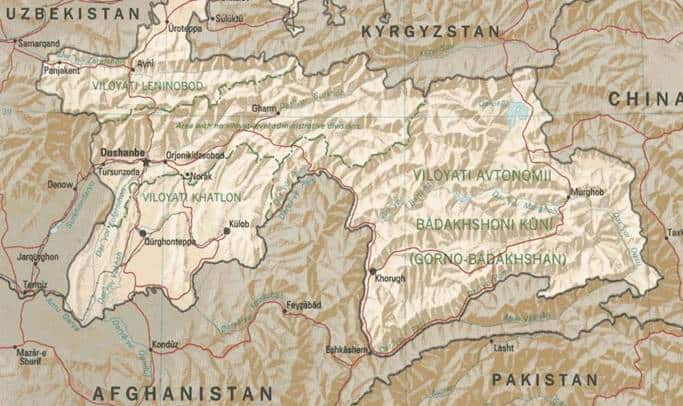

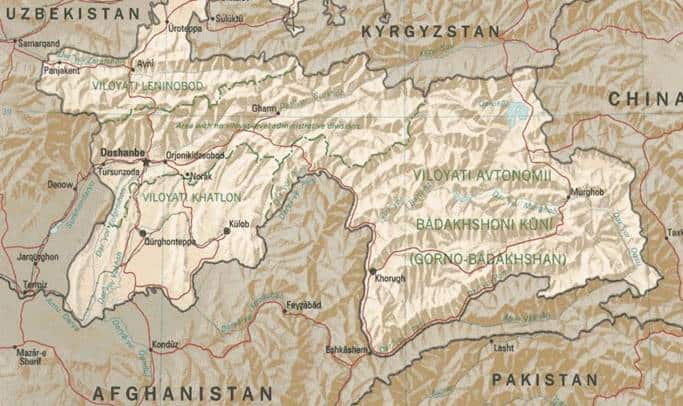

As fascinating as the geology is, the people here are more interesting. The Pamir Knot is primarily in the southeast corner of Tajikistan, a region called Gorno-Badakhshan.

While the four other “Stans” of the former USSR (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan) are ethnically Turkic, Tajikistan is not. Tajiks are ethnically Persian and speak a Persian dialect called Dari. They are, however, not Shia Moslem like the Persians of Iran, but Sunni Moslem instead.

While the four other “Stans” of the former USSR (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan) are ethnically Turkic, Tajikistan is not. Tajiks are ethnically Persian and speak a Persian dialect called Dari. They are, however, not Shia Moslem like the Persians of Iran, but Sunni Moslem instead.

However, the people who live in the Pamir Knot are, I discovered, very different from other Tajiks.

Among themselves, the inhabitants of the Pamirs call themselves “Macedonians.” Most have fair skin with red, light brown, or even blonde hair, and blue or green eyes. They consider themselves the descendants of Alexander the Great’s Greeks and those of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. Here’s a young Pamirian girl:

They speak an “Avestan” language which is that of the ancient scriptures of Zoroastrianism, the religion of all Central Asia until it was replaced by the sword of Arab Islam in the 6th-7th centuries. Here is an anatomically correct statue of Ahura-Mazda, the god of Zoroastrianism, from about 500 AD (picture taken in the Dushanbe Museum):

They speak an “Avestan” language which is that of the ancient scriptures of Zoroastrianism, the religion of all Central Asia until it was replaced by the sword of Arab Islam in the 6th-7th centuries. Here is an anatomically correct statue of Ahura-Mazda, the god of Zoroastrianism, from about 500 AD (picture taken in the Dushanbe Museum):

The kind of Islam practiced by Pamirians is permeated with elements of Zoroastrianism, such as the worship of fire. Here is the entrance to the burial shrine of an Islamic saint in the Wakhan, next to which is an altar for sacred ceremonial fires:

The kind of Islam practiced by Pamirians is permeated with elements of Zoroastrianism, such as the worship of fire. Here is the entrance to the burial shrine of an Islamic saint in the Wakhan, next to which is an altar for sacred ceremonial fires:

That kind of Islam in the Pamirs is called Ismailism. Ever hear of the Aga Khan? That’s the title of the spiritual leader of the Ismailis (iss-my-lees), who believe in a mystical, peaceful form of Islam that is the antithesis of hate, violence, and Sharia imperialism that infuses mainstream Sunni or Shia Islam.

That kind of Islam in the Pamirs is called Ismailism. Ever hear of the Aga Khan? That’s the title of the spiritual leader of the Ismailis (iss-my-lees), who believe in a mystical, peaceful form of Islam that is the antithesis of hate, violence, and Sharia imperialism that infuses mainstream Sunni or Shia Islam.

There are no mosques in the Pamirs, because Ismailis have no mosques. They pray privately – men and women together. Ismaili men are extremely respectful of women. The thought of treating women as an inferior form of humanity as does mainstream Islam is as disgusting to Ismaili men as it is to us. No Ismaili man would even think of demanding his wife wear a veil or cover her face in public.

The Ismaili Pamirians are among the most friendly and hospitable people I have ever met around the world. They always have a smile for you, a stranger, and the smile is genuine. At any opportunity, they will invite you into their home for a cup of tea and bowl of yogurt. You are not an infidel to them, but a fellow human being and their guest.

Up in these lost mountains on the roof of the world, there is a form of Islam that should be a model for Moslems all over the world, a moral contrast to the medieval evil of Wahhabi Islam of the Saudis, the Deobandi Islam of the Taliban, or the Khomeini Islam of the Mullahs of Iran.

There are Ismaili Moslems in dozens of countries all over the earth – but the greatest concentration of them is here in the Pamirs. It is geopolitically ironic. Let’s take another look at the Tajikistan map above:

Note the present border of Tajikistan’s Gorno Badakhshan, and Pakistan is separated by a finger of Afghanistan reaching all the way to China. That’s the famed Wakhan Corridor, drawn in 1895 to keep the expanding Russian Empire from physically touching British India. These borders are an artifact (as are many others around the world) of 19th-century colonial geopolitics.

Note the present border of Tajikistan’s Gorno Badakhshan, and Pakistan is separated by a finger of Afghanistan reaching all the way to China. That’s the famed Wakhan Corridor, drawn in 1895 to keep the expanding Russian Empire from physically touching British India. These borders are an artifact (as are many others around the world) of 19th-century colonial geopolitics.

I just drove through the Wakhan, which is, in places, only a few miles wide. Here is a picture of three countries: Tajikistan in the foreground, Afghanistan on the other side of the Amu Darya, the snow-clad Hindu Kush mountains of Pakistan in the distance.

Marco Polo’s route to China was through the Wakhan in 1273. It was a strategic valley to the Bactrian Greeks, who built this castle-fortress overlooking it over two thousand years ago:

Marco Polo’s route to China was through the Wakhan in 1273. It was a strategic valley to the Bactrian Greeks, who built this castle-fortress overlooking it over two thousand years ago:

If you look down the Wakhan, you can see way in the distance on the Afghan side a small dot that looks like a building (center of the picture on the edge of the Amu Darya/Oxus river). There is nothing around it.

If you look down the Wakhan, you can see way in the distance on the Afghan side a small dot that looks like a building (center of the picture on the edge of the Amu Darya/Oxus river). There is nothing around it.

Turns out, it’s a secret CIA interrogation prison for captured Taliban. Here it is up close from the Tajik side of the river:

Turns out, it’s a secret CIA interrogation prison for captured Taliban. Here it is up close from the Tajik side of the river:

We’ll discuss Afghanistan next week (hint: this colonial construct is not “the Graveyard of Empires” – that’s a myth. The reality is that for millennia it’s been the Doormat of Empires.)

We’ll discuss Afghanistan next week (hint: this colonial construct is not “the Graveyard of Empires” – that’s a myth. The reality is that for millennia it’s been the Doormat of Empires.)

Suffice it to say, there are as many Tajiks in Afghanistan as there are in Tajikistan, well over 8 million – more than a quarter of the population of Afghanistan. The majority live in the north of the country, where Afghanistan and Tajikistan share 750 miles of border.

In the capital of Tajikistan, Dushanbe, the most prominent monument is to the country’s national hero and founder of the Tajik nation, Ismail Somani (ruled 892-907).

The Somonid Empire he founded at its peak in the 10th century contained all of present-day Afghanistan and Tajikistan, plus most of Uzbekistan and the eastern half of Iran: over one million square miles. Tajiks view themselves as the heirs to the Somonid Empire. Their currency, the somoni, is named after the empire’s founder.

The Somonid Empire he founded at its peak in the 10th century contained all of present-day Afghanistan and Tajikistan, plus most of Uzbekistan and the eastern half of Iran: over one million square miles. Tajiks view themselves as the heirs to the Somonid Empire. Their currency, the somoni, is named after the empire’s founder.

Afghan and Tajikistan Tajiks speak the same Dari dialect of Persian, and most all ascribe to the Sunni version of Islam. While the rest of the country is Sunni, the Shia Ismailism of the Pamirs has had a distinctly moderating influence. The Aga Khan periodically visits the Pamirs. At the main Pamir town of Khorog on the Amu Darya, he delivers a sermon with huge loudspeakers as Afghan Ismailis assemble by the many thousands on a gravel floodplain across the river to hear him.

But why doesn’t he just cross the footbridge nearby into Afghanistan and talk to his Afghan followers directly? Because the Afghan government in Kabul won’t allow it. It’s afraid that the Aga Khan might provoke the Afghan Ismaili Tajiks into rebelling and demanding to merge their lands with Tajikistan.

Yet, that is the precise opposite of what HH Aga Khan IV – personal name, Mawlana Hazar Imam – preaches. He constantly stresses the principal virtues of Ismailism: Modesty, Patience, Humility, Knowledge, Forbearance, and Consultation.

Thus, the great irony to be found here. The Pamir Knot, one of the remotest places on earth, is where we might find a solution to peacefully unravel so much of the world’s religious dissension.

In any regard, it is in so many ways an unforgettable experience to be here, one that I’ll always treasure. If I return, I’ll invite you to come with me.

©2019 Jack Wheeler – republished with permission

Like Our Articles?

Then make sure to check out our Bookstore... we have titles packed full of premium offshore intel. Instant Download - Print off for your private library before the government demands we take these down!