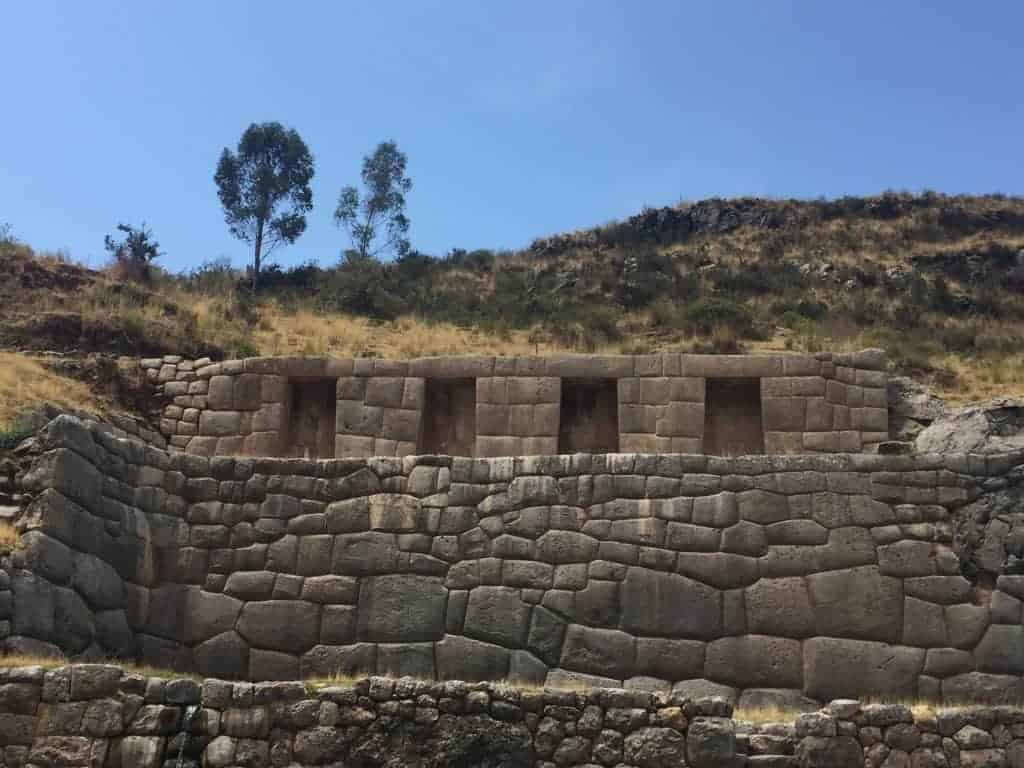

We came down through the hillside by van, pitching in the cuts of the mountain. Since dawn, we had been in Saksaywaman, an Inca citadel dating back to the 13th century. I was still trying to wrap my head around the dizzying architecture, the truck-sized boulders chiseled into cubes and perfectly stacked like legos. I could barely fit my rain gear into my backpack, but the Incas were crafting stone fortresses nine-hundred years ago? Perspective is a bitch.

By noon I was in Cusco, the last major foothold of civilization in the Peruvian Andes. I had come to the country to hike the Inca Trail, a four-day trek through mountains to the famed Machu Picchu, but I’ve never gone anywhere that food wasn’t an underlying motivation. As a young, ambitious cook, I had grown weary of my years working in Paris and New York City. There was glamor, prestige of course, but my soul needed a temporary respite from the chef’s whites and the foie gras. Peru offered something different, something new. For the past few years, Peru had been on the minds of most chefs back in the States. Acclaimed restaurants such as Central and Astrid y Gastón had skyrocketed up the ladder and settled themselves firmly among the best on the planet. I wasn’t concerned as much with these places, however, mostly because I was broke and my suit and tie didn’t make the packing list, but what the emergence of these world-class restaurants did was cast a light on what Peruvians had known for a thousand years – the food was fantastic.

Cusco provided an alluring combination of past and present. It was a city, preserved enough to maintain its culture and modern enough so that food was more than just a stark means of survival. I knew I wanted to avoid the brick-and-mortar and focus on the lively street food scene so synonymous with South America. I began in the Plaza de Armas, a sprawling square in the center of the city. A place to get your bearings. I rested in the shadow of the Basilica of the Assumption and surveyed the masses. Old Peruvian women with felt hats and woven ponchos walked their llamas through herds of German backpackers, dreadlocked hippies, and enterprising teens pushing knockoff artwork. The elevation was kicking in, and my throbbing head felt every inch of the eleven-thousand-feet. My guide in Saksaywaman had told me that the locals used coca leaves, the natural ingredient found in cocaine, to alleviate the burden of their gravity. There were two ways to consume the contraband: steep the leaves in hot water and drink it like tea or chew them raw like tobacco.

A ten minute walk from the Plaza de Armas, and I found myself on a dusty street lined with shops and watering holes that weren’t open yet, or ever. A half-dozen wild dogs ran past, snapping at each other’s tails, and beyond them I saw two grizzled men sitting on the steps of a door marked “Bar.” They were glossy-eyed and leather-skinned, with wads of coca in their cheeks so big that their mouths were agape, and thick, brown saliva dripped down their chins. They eyed me up and down with dismissive glances, but I flashed a few nuevo sol and they reluctantly parted with a bag. I didn’t know what to expect. A stimulant-fueled race through my oxygen deprived veins, muscles twitching in discordance, synapses flickering that hadn’t been lit in years. I chewed a handful of the leaves and waited. Nothing. In the end, it tasted like, well, leaves. Gringo immunity, I thought. There was a slight numbing of the gums and my headache eased, so I chalked it up as a success and made my way in search of something to eat.

A few blocks from my botched drug deal, I came to the Mercado de San Pedro, a huge open-air market with what seemed like hundreds of vendors selling everything from alpaca fur, to boiled goat heads, to wooden chess sets. The first thing I noticed was the color. Rows of bananas and citrus glistened with vibrant yellows and oranges. The flavors were familiar, yet somehow clearer, more direct. I walked past baskets of potatoes and beans in ambers, browns, and purples. Fresh white cheese, pressed into discs, smelled deliciously soured. Made from raw cow’s milk, it crumbled like soft feta without the the brine. Near the center of the market, the scent of smoke and meat wafted from a makeshift grill. A stout, brown woman flipped skewers and tended coals. I bought a few pieces and she handed them to me on parchment paper. “Alpaca,” she said with a smile, deducing that it was a first for me. The meat was soft and rosy, like good veal, with that barnyard gaminess that only alternative animals provide. A thick paste of garlic, black mint, and a hot red chili called rocoto were ground together in a mortar and slathered on the charred meat like clay. I washed it down with a few cups of pisco, a liquor native to Peru and Chile. Similar to a brandy, pisco is a colorless grape wine distilled to a proof high enough to catch you off guard. Meaning “bird” in Quechuan, an indigenous language spoken in the Andes, pisco can be served straight or, in swankier settings, shaken with egg whites and lime to create a pisco sour. Straight, the liquor is sweet and fire at the same time. I drank a half bottle’s worth before realizing the error of my ways. The only way to stave off my pisco stupor was with more food, so I went in search of Peru’s most infamous of local delicacies.

I found my prize just away from the buzz of the market, where a little cart was selling roasted cuy. What could only be described to English speakers as guinea pig, cuy are larger and meatier than their classroom-pet cousins up north. Here, the cuy were the size of cats and spit roasted until the meat was tender and the skin crackled like rodent bacon. The woman behind the cart took a few of my coins and hacked a portion of the cuy into bite-sized pieces with a cleaver. The first thing I noticed was how well it was cooked. Clearly, this wasn’t her first guinea pig. The skin was salty and delicious, and it shattered in my mouth as I chewed. The meat itself was dark and unctuous like roasted pork, though stringier and bit oily. There was an obvious aroma that distinguished the cuy from more common meats. It was nothing off-putting, but present enough for Mother Nature to remind me that I was eating a giant rat. I wrestled with the notion for a minute, but the meat was tasty enough to make me quickly forget.

Experience the Insider community that takes your international lifestyle to the next level. Download your FREE guide

"18 Steps to Implementing Your Plan B" instantly!

The pisco was starting to get on top of me, so I stumbled to the back of the market where there was a row of wooden benches and a counter offering soup to the weary. I took a seat beside a shoeless Andean man who looked like he had tasted the pisco himself, and I pointed to his bowl when the cook asked me for an order. What came was hot and good. Stewed chicken thighs, boiled yellow potatoes, and choclo (a native corn variety with kernels the size of dimes), in a rich broth spiked with cilantro. I came at the soup with the ferocity of a dog protecting his bowl, hunching over as if to keep even the sight to myself. I ate until the soup was only bones and the hot broth swished in my stomach like the tides of the Pacific. I sat up, clear minded and aware of my surroundings. The shoeless man next to me nodded in stoic assurance that no one on earth was eating better than us.

Outside the market, women danced in honor of the sun. They shook and clapped in wide, rainbow-colored dresses that swirled like kaleidoscopes. The music was rhythmic, with an overlap of pan flute that was charming in its native environment but would make you cringe on an elevator. I waded through the crowd. The musicians, the dancers, the stray dogs. The children carrying baby alpaca with them like puppies, using them as a cute misdirection while they picked pockets. I bought a small bag of churros, warm and dusted in cinnamon sugar. I was already full, but excess is a medicine best taken in large doses.

The sun hung low in the sky then, and a cool breeze came down from the hills. I walked the stairs up to Norton Rat’s Tavern, a traveler bar that overlooked the southeast part of the Plaza de Armas. I got myself a cheap bottle of Cusquena and perched out over the balcony. Inside, dozens of flags hung from the ceiling as offerings from those who had come before. A group of rowdy Australians sat in the corner, badmouthing the refs of a rugby match that they watched on a grainy television feed. But outside on the balcony I was alone, at peace. I thought to myself, was there any other life but this one? I looked out beyond the city to the outline of rocky peaks in the distance, and I knew I didn’t have the answers. I wouldn’t like them if I did. So I sipped my beer, checked the map, and offered my soul to the gods of the mountain.

Like Our Articles?

Then make sure to check out our Bookstore... we have titles packed full of premium offshore intel. Instant Download - Print off for your private library before the government demands we take these down!