Navigating a Country Where the Streets Have No Name

My first clue at the topsy-turvy nature of the Nicaraguan address system should have been what I was told to do at the airport. I was advised to have the address of where I would be staying ready in case they asked me for it while going through Customs & Immigration – but as far as I could tell, there wasn’t an actual address involved. In translation, the “address” I had been given read something like “[neighborhood name], near [restaurant name], two blocks east of [business name]” – not exactly as clear as, say, “221B Baker Street, London.” It didn’t make much sense to me, but it seemed perfectly reasonable to the immigration officer, who waved me through without a second glance at the strangely worded location on my entrance card. Already mildly on edge about the whole airport process, I didn’t have much brainpower left to devote to the issue, so I let it go for the moment.

I was lucky enough to be picked up directly at the airport and driven to my new apartment right away, so I didn’t encounter the address issue again for a while. Had I been paying closer attention, I might have noticed that we turned onto a street without a sign and walked into a house with no number, but it was dark and my mind was elsewhere. That first night, I settled into my new home without knowing exactly where I was, geographically speaking, but without worrying too much about it.

The streets of Nicaragua are not particularly neat, either in organization or in substance. The streets of many major cities, from as far back in history as Mohenjo-daro in 2600 BC and Babylon in the 18th century BC, follow a distinct grid system, wherein streets are built at right angles and the layout is relatively logical; not so in Managua, where roundabouts and winding avenues are the norm. These streets aren’t particularly well maintained, either, unpaved in certain sections or laid with crumbling pavement that makes for quite a bumpy ride. But to give credit where credit is due, Managua wasn’t always this way; its streets were relatively modern and followed a clear grid pattern until 1972, when an earthquake displaced a quarter million residents and tore the city into unrecognizable pieces.

In the Central American tradition of making do with what they have, Managuans have since replaced their old, traditional address system with an ad hoc way of describing locations. In an era of GPS and Google Maps it can be jarring, but also quite charming, to see local restaurants describe their locations as “one block west of the traffic lights at Santa Ana Church” or “two blocks south of the convent, half a block east of the college, in front of the bank.” Taxi drivers are masters of this system; whereas London black cab drivers must study for years to master The Knowledge, Nicaraguan drivers have to know without asking how to get to any number of restaurants, the country club, grocery stores, and all the back streets that have no particular landmarks to guide them.

Not only do Nicaraguan cabbies have to know their local geography, they also have to know a fair bit of history as well. Although the system of landmarks in Managua that emerged post-earthquake relied on the most obvious features of the area, things change over time; for example, a little tree may now be a very big tree, and a business that once stood on the corner may have been sold, renovated, or torn down. Nevertheless, tradition dictates that if a landmark was good enough before, it’s still good enough now – even if it no longer actually exists. While an out-of-towner might be confused about being directed to a blue house that is actually brown, a local will know that it used to be blue, and that’s good enough.

As if it weren’t enough to ask all taxi operators to have a functioning mental map of a city’s major and not-so-major locations, both past and present, there’s a particular code that some Nicaraguans employ when giving directions that isn’t obviously translatable, even to someone with a better working knowledge of Spanish than I have. Al norte, al sur, al oeste, al este are fairly straightforward cardinal directions: to the north, south, east, and west. However, there are a few surprises thrown into the mix. Rather than east and west, it’s common for Nicaraguans to use either “abajo” or “arriba.” Normally, these mean “down” or “up,” but when giving directions, they mean “west” and “east,” a code that can be unlocked only by understanding the pattern of the sun, which rises (or goes up) in the east and sets (or goes down) in the west. Get it now? Good, because there’s more.

Managua has its own major lake, called Lake Managua or Lake Xolotlán, which many residents refer to as a cardinal direction of its own. “Al lago,” or “to the lake,” means north in Managua – but in other cities where the lake is elsewhere, of course, it could mean something entirely different. More straightforward are addresses like those of the United States embassy in Managua, for example, which can be found at Carretera Panamericana Sur km 5.5, or five-and-a-half kilometers along the Pan-American Highway South. Straightforward, unfortunately, doesn’t mean specific; although the embassy presents a large, concrete facade that’s difficult to miss, locating buildings by the half-mile on a highway usually isn’t the most exact way to denote an address.

For more particular directions, particularly when walking, some addresses include meters, which should be familiar to all users of the metric system. However, to further complicate matters, Central Americans have their own unit called the vara, borrowed from an old Spanish colonial measurement system. The length of a vara itself varies, having been “standardized” at different measures in different locations at different times; one vara can be anywhere from 32.91 to 34.1 inches, but can generally be rounded to just over one yard.

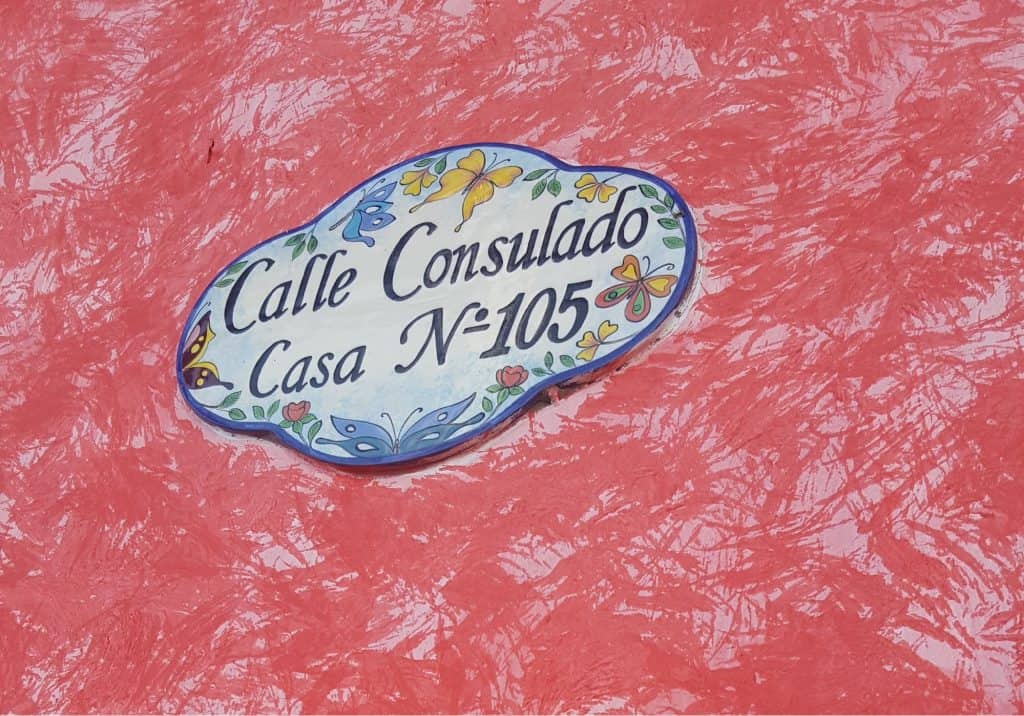

It’s not quite true that street addresses don’t exist in Nicaragua, just that people tend not to use them. In Granada, for example, many of the colorful buildings lining the streets had a plaque affixed to their side, denoting a clear street name and house number. However, Granada’s system is the exception in the country, rather than the rule. Even in post-earthquake Managua, I technically have a street address, or so Google Maps tells me – but what good’s an address if no one knows where it is? At least, that’s what the Nicaraguans thought when their national postal service proposed reinstating the old system of street names and numbers a few years ago. No thanks, they said, our system works just fine. It may take some getting used to, but if it’s good enough for Nicaragua, it’s good enough for me.

Like Our Articles?

Then make sure to check out our Bookstore... we have titles packed full of premium offshore intel. Instant Download - Print off for your private library before the government demands we take these down!