Brazil, the Country of the Future?

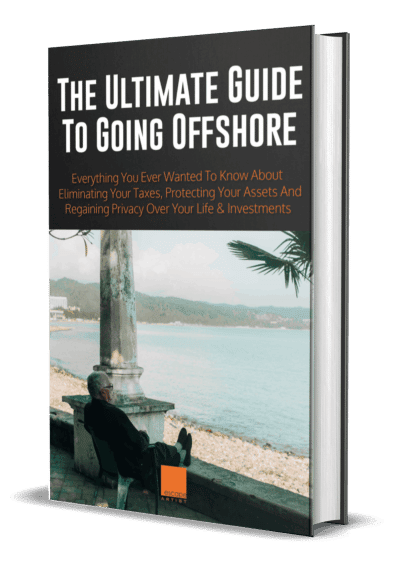

There’s a popular saying that “Brazil is the country of the future.” The logical problem is that such a future never arrives, even if there are occasional glimpses. In 2009, the Economist featured the country on the cover of its November 2009 edition as the next miracle “take-off.” Less than four years later, the same magazine took the opposite view with the caption, “Has Brazil blown it?” What happened in those four short years?

Source: Economist Magazine

There was optimism going back even further. In 2001, economists at an investment bank, Goldman Sachs, coined the term BRIC, bracketing Brazil along with Russia, India, and China, as the economies that would inevitably come to dominate the world in the coming years. The Economist article cited a prediction from PwC, a consultancy, that by 2025, São Paulo would be the world’s fifth-wealthiest city.

In hindsight, such optimism was predictable. As a sign of its economic ascent, in 2007, the country was selected to host the 2014 World Cup, and in 2009, Rio de Janeiro was selected to host the 2016 Olympic Games.

These two announcements coincided with a period when the economy was expanding rapidly: 7.5% in 2010, the year before Rousseff took office from Lula. Inflation was finally under control and the good times meant that the Workers’ (PT) Party government spent like there was no tomorrow, with little accountability.

Under the Workers’ (PT) Government, led by Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (Lula), a former trade-union leader, the country was making great strides in reducing inequalities that have plagued Brazil since its Colonial Portuguese times. He was hailed as one of the world’s most popular politicians as he pushed the Bolsa Familia program, a poverty relief initiative that distributed cash to about 12 million lower-income Brazilian families.

Brazil Strikes Oil![drilling for oil in the ocean]()

To top it all off, starting in 2005, geologists and engineers at Brazil’s mixed economy oil company, Petroleo Brasileiro

(Petrobras), uncovered massive “pre-salt” oilfields off its Atlantic coast, lying under at least a two-kilometre thick layer of salt. It was not just about the depth of the fields, but also the distance, as the oil fields are some 340 km from shore, measuring 800 km in length and 200 km in width, extending along the coastline of five states. According to Petrobras engineers, the type of oil discovered is of generally premium quality (light sweet crude), making it ideal to refine into useful products, such as petroleum naphtha, gasoline, diesel fuel, jet fuel, asphalt base, heating oil, kerosene, and liquefied petroleum gas.

This was the biggest deep-water offshore discovery in decades. At the time representing the main El Dorado for oil and gas sector investments. Petrobras officials envisioned a plan that would give Brazil elite status among the world’s energy producers, including (at the very least) energy independence, since the country was spending a considerable amount importing distillates.

Politicians hailed a new era which would propel the country’s modernization. Based on the criteria set by the Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE) and Brazil’s own National Petroleum Agency, the last figures indicate that Petrobras has 13.3 billion barrels of proven oil and gas reserves, ranked 2nd behind Venezuela in Latin America and 15th in the world. Unproven oil and gas reserves may account to two or three times this figure.

To exploit these proven deep-water oil fields, Petrobras required significant and rapid financial investments. From 2008, the company conducted an unprecedented capital increase by issuing billions of shares and then calling for investments totalling some $224.7 billion, just for the period between 2011 and 2015. Petrobras’ investment grade made it relatively easy to raise such large amounts of funds, especially during the continued low-interest rate environment in Europe and the United States. By September 2013, Petrobras reported gross debts of more than $135bn, making it the world’s most indebted oil producer.

To exploit these proven deep-water oil fields, Petrobras required significant and rapid financial investments. From 2008, the company conducted an unprecedented capital increase by issuing billions of shares and then calling for investments totalling some $224.7 billion, just for the period between 2011 and 2015. Petrobras’ investment grade made it relatively easy to raise such large amounts of funds, especially during the continued low-interest rate environment in Europe and the United States. By September 2013, Petrobras reported gross debts of more than $135bn, making it the world’s most indebted oil producer.

However, the debt didn’t worry many stakeholders, since Petrobras’ board of directors and its investors were confident that their investment would pay off. Economists forecasted that the benchmark crude oil would remain steady at $85+/barrel, thus ensuring a healthy margin as the average extraction costs at pre-salt fields were roughly $45/barrel. According to Petrobras’s president at the time, José Sergio Gabrielli, total production would rise from two million barrels a day in 2010 to 5.3 million in 2020. However, Petrobras recently informed that its total oil and natural gas production in October 2016 was 2.81 million barrels of oil equivalent per day.

Experience the Insider community that takes your international lifestyle to the next level. Download your FREE guide

"18 Steps to Implementing Your Plan B" instantly!

The First Signs of Trouble at Petrobras – Pasadena Where You At?

The first real signs of something fishy going on at the oil giant came in 2007. It emerged that Petrobras overpaid in its purchase of Pasadena Refining Systems Inc., a 100,000 barrel a day refinery based in Texas, in a series of transactions dating back to 2006. According to Brazilian prosecutors and court records, Petrobras paid about $1.2 billion for the refinery complex, which is almost 30 times the amount the Belgian company Astra Oil purchased it just one year earlier. A team of police and prosecutors have found evidence that a Belgium trading company paid $15 million in bribes to secure the sale of the Pasadena refinery to Petrobras.

The first real signs of something fishy going on at the oil giant came in 2007. It emerged that Petrobras overpaid in its purchase of Pasadena Refining Systems Inc., a 100,000 barrel a day refinery based in Texas, in a series of transactions dating back to 2006. According to Brazilian prosecutors and court records, Petrobras paid about $1.2 billion for the refinery complex, which is almost 30 times the amount the Belgian company Astra Oil purchased it just one year earlier. A team of police and prosecutors have found evidence that a Belgium trading company paid $15 million in bribes to secure the sale of the Pasadena refinery to Petrobras.

Unfortunately, Pasadena was only the tip of the iceberg, as authorities began to untangle a complex web of high-worth contracts that became the biggest corruption scandal in Brazil’s history – and one of the biggest ever in corporate history. Soon, damaging details emerged of the extent of the corruption scheme at other refineries, including the Abreu e Lima refinery construction, which was $20 billion over budget and running three years behind schedule.

A Luxury Land Rover Gift Leads to Something More Sinister

Although Petrobras is a publicly-traded Company, politicians, not shareholders, get the final say on who fills high-level management positions. These high-level positions are inevitably filled by politicians and close allies to politicians. In fact, ex-president President Dilma Rousseff was on the Petrobras’ board of directors (placed there by a close ally, former President Lula) and signed off on the purchase of the Pasadena refinery.

Another close ally to the Partido Progresista (PP) and Worker’s (PT) Party was Paulo Roberto Costa, who in 2004, was  nominated to a director position within Petrobras’s downstream department. In 2013, Brazilian police began to investigate details behind a luxury Land Rover car which was in hindsight carelessly gifted by his friend, lawyer & accomplice, Alberto Youssef (a career criminal who was already under investigation). Upon raiding the home of Mr. Costa, police uncovered half a million dollars in cash and, more crucially, mountains of evidence to something much more sinister that was going on at Petrobras.

nominated to a director position within Petrobras’s downstream department. In 2013, Brazilian police began to investigate details behind a luxury Land Rover car which was in hindsight carelessly gifted by his friend, lawyer & accomplice, Alberto Youssef (a career criminal who was already under investigation). Upon raiding the home of Mr. Costa, police uncovered half a million dollars in cash and, more crucially, mountains of evidence to something much more sinister that was going on at Petrobras.

In exchange for reduced sentences, both defendants agreed to cooperate with authorities on the terms that they revealed everything, via a plea bargain agreement. They proceeded to provide authorities with a goldmine of documents and information. Mr. Costa named more than 40 politicians from a spectrum of political parties, detailing how while he was Downstream Director at Petrobras from 2004 to 2012, dozens of politicians received up to 3% commissions on the values of multi-million dollar contracts signed with Petrobras. A considerable amount of the extra revenue from the over-inflated contracts was allegedly funnelled to political parties, including to Lula’s and Rousseff’s left-wing Workers’ (PT) Party, with some of the money directly going to fund election campaigns. Investigators uncovered funds that went to politicians and Petrobras executives, which were dispersed to bank accounts in Switzerland, Monaco, and Panama. Beneficiaries went on lavish shopping sprees, including purchasing properties in the UK.

In June 2015, the chief executive of Petrobras, Maria das Graças Silva Foster, Petrobras’ first female CEO, as well as five members of the state-run oil giant’s board of directors were forced to resign.

Brazil’s Version of House of Cards – Operation Car Wash (Lava Jato)![Federal Judge Sergio Moro]()

What was supposed to be a relatively small corruption investigation involving initially just one Petrobras Director over a gift, rapidly grew into Brazil’s biggest and most shocking scandal to date. This operation, which is still going strong, is called Operation Car Wash (or Lava Jato in Portuguese), as some of the money had been laundered through an actual car wash establishment.

Since March 2014, prosecutors led by Federal Judge Sergio Moro, a specialist in white-collar crime have accused more than 110 high-profile politicians and business executives of financial crimes, as well as six construction and engineering firms. Each arrest allowed prosecutors to gather more evidence through plea bargain & leniency agreements as permitted under Brazilian law. Prosecutors advise defendants that to qualify for a plea bargain, they must be prepared to offer unique privileged information, thus raising the bar and uncovering more dirt.

In October 2015, Andre Esteves, the Brazilian billionaire who transformed BTG Pactual into the largest independent investment bank in Latin America, was arrested as he allegedly tried to interfere in testimony related to a pay-to-play scheme. Next, in March 2016, Marcelo Odebrecht, the former chief executive officer of South America’s biggest construction company, Odebrecht, was sentenced to 19 years in prison for bribery. The latest from Odebrecht is that he has agreed to plea bargains and a massive leniency deal under which the company would pay around $2.1 billion in fines for its role in the corruption scandal.

In October 2015, Andre Esteves, the Brazilian billionaire who transformed BTG Pactual into the largest independent investment bank in Latin America, was arrested as he allegedly tried to interfere in testimony related to a pay-to-play scheme. Next, in March 2016, Marcelo Odebrecht, the former chief executive officer of South America’s biggest construction company, Odebrecht, was sentenced to 19 years in prison for bribery. The latest from Odebrecht is that he has agreed to plea bargains and a massive leniency deal under which the company would pay around $2.1 billion in fines for its role in the corruption scandal.

The message that Judge Moro is sending out is clear – nobody is immune from investigation and prosecution, no matter how wealthy and powerful the individual.

According to a lead prosecutor, the total amount of money involved in the corruption scheme could exceed $5.3 billion, dwarfing the scandal at FIFA of just $200 million which led to the resignation of ex-FIFA president Sepp Blatter. The scandal, which still has legs to run, has gripped Brazil and rocked the country socially, economically, and politically.

Dilma Rousseff Impeachment Proceedings![marchers in Brazil]()

In 2013, full facts emerged on the extent of the corruption scheme, leading to millions of angry Brazilians taking to the streets. Millions took to the streets calling for Dilma’s impeachment and for Lula to be jailed. Together with ending corruption, Brazilians demand more investment in education, infrastructure, healthcare, and security.

A minority remain loyal to the Workers’ (PT) Party and were against regime change, labelling the impeachment proceedings as a “coup attempt.” Some protestors went as far as to call for a return to military rule. The country remains deeply divided along party lines.

Although Dilma has so far been cleared of any links to the Petrobras scandal, her political mentor and former president, Lula da Silva, and many within the Workers (PT) Party were directly involved in the corruption scheme. Also caught up in the web are a wide spectrum of other political parties.

In March 2016, in a strange twist reminiscent of the hit show House of Cards, Dilma unsuccessfully attempted to appoint Lula to a Cabinet position, suggesting that she was abusing her power by trying to shield him from prosecution in the Petrobras scandal. As it turned out, a Brazilian judge ordered the government to release a wiretap recording of Rousseff speaking to Lula. Sometimes fact is stranger than fiction.

In March 2016, in a strange twist reminiscent of the hit show House of Cards, Dilma unsuccessfully attempted to appoint Lula to a Cabinet position, suggesting that she was abusing her power by trying to shield him from prosecution in the Petrobras scandal. As it turned out, a Brazilian judge ordered the government to release a wiretap recording of Rousseff speaking to Lula. Sometimes fact is stranger than fiction.

Since the scandal emerged, the image of the Workers’ (PT) Party has been particularly tarnished, as it was meant to be a party which represented the interest of the common worker, in stark contrast with the traditional corruption carried out by Brazil’s “white elite.”

Eventually, the public outcry was too much and impeachment proceedings commenced in 2015 on grounds that she cooked the government’s books to hide the scope of Brazil’s deficit problem during her 2014 re-election campaign – an otherwise quite common occurrence in Brazil, but for the (unrelated) Petrobras scandal.

After all was said and done, Dilma was finally impeached in May 2016. Subsequently, a caretaker interim president, Michel Temer, took over from Dilma until the present day. The next general Brazilian elections will be held in October 2018, and the Workers’ (PT) Party is projected to have a poor result.

Yet another irony occurred in October 2016, when the former speaker of the lower house, Eduardo Cunha, who orchestrated the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff, was arrested on corruption charges. He is accused of taking $37m in bribes as part of the Operation Car Wash investigation.

Enjoy this podcast from The Expat Money Show – JohnnyFD who talks about moving from the USA and living in Bali and Thailand.

From Boom to Bust

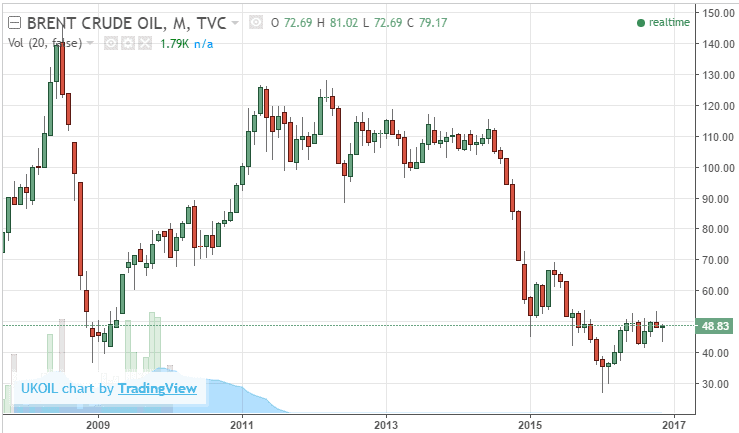

Brazil has always been a major exporter of commodities, including iron ore and perishables like soybeans and beef. In 2015, a perfect storm was brewing as China’s insatiable appetite for commodities began to cool. At the same time, oil prices collapsed, in large part as a result of the American shale-oil revolution and a refusal by OPEC to cut oil production. The wind was suddenly taken out of the sails of the country’s economy and hit both Petrobras and Brazil hard.

Brazil has always been a major exporter of commodities, including iron ore and perishables like soybeans and beef. In 2015, a perfect storm was brewing as China’s insatiable appetite for commodities began to cool. At the same time, oil prices collapsed, in large part as a result of the American shale-oil revolution and a refusal by OPEC to cut oil production. The wind was suddenly taken out of the sails of the country’s economy and hit both Petrobras and Brazil hard.

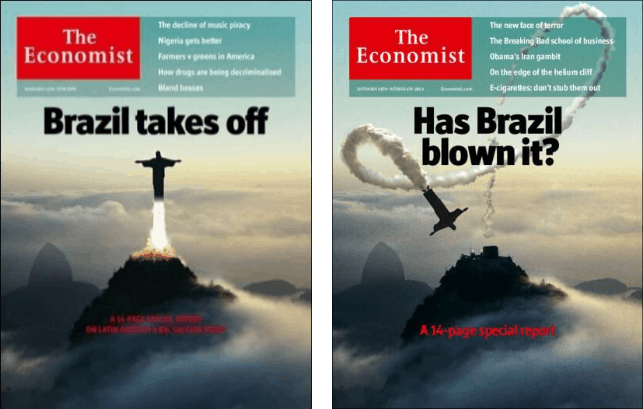

Brazil’s economy shrank 3.8% in 2015, the biggest drop since 1990. The economy is expected to fall by a further 3.2% in 2016. The government recently lowered its 2017 growth forecast from 1.7% to 1%.

According to a study done by the Getulio Vargas Foundation’s Environmental Solutions and Infrastructure Group, the Petrobras scandal alone has cost Brazil a little more than 1% of its GDP ($27.1 billion).

Statistics look bleak as according to the Brazilian Central Bank. As of September 2016, inflation remains stubbornly high at an annual pace of 10.6%, interest rates are kept at 14.25%, and the unemployment rate has climbed to 11.8% as of September 2016.

The collapse in the price of crude oil has hurt Petrobras’ margin, making the discoveries of large offshore oil reserves less profitable. The price of crude oil has since stabilized at around $48/barrel (November 2016), making the pre-salt production only marginally profitable, but well below assumptions made in 2012. This drop is reflected in Petrobras’s current share price, although it has recovered since its January 2016 lows. The price remains far off the highs reached in 2008.

Petrobras’ share prices has lost considerable value since full details of the scandal emerged in 2013

The Worst Appears to be Over

According to Marcelo Rabelo, analyst at leading Latin American think tank and higher educational institution, Fundação Getulio Vargas (FGV), the worst may be over:

“Despite deep-rooted corruption problems of the last decades, Petrobras has shown robustness. The latest figures from the National Petroleum Agency (ANP), reflect a sustainable growth in its proven reserves extracting activities in its pre-salt fields amounting to a record one million barrels a day. The question still remains on how Petrobras will reduce its debt obligations, while attracting new investors to continue its expensive exploration of the pre-salt fields. Importantly, the company must act towards national interests and ensure that its management is autonomous and free from harmful political influence. These challenges come at a period in the country when the current government lacks political legitimacy following the controversial impeachment of Dilma Rousseff earlier this year.”

The Era of Impunity is Ending

Corruption has always been a problem in Brazil, perhaps due to its legacy as a Portuguese exploitation colony of its natural resources, notably gold, sugar cane, and coffee. For hundreds of years, it was nearly impossible to prosecute a high-level official or politicians for crimes related to corruption. However, the latest series of scandals to engulf Petrobras could positively signal that this era of impunity is ending. It appears that Brazil has finally evolved to seriously tackle its corruption problem. In addition, the fact that millions took to the streets, not just to party but to protest is also positive and a sign of a maturing democracy.

The latest round of high-profile arrests, this time unrelated to Operation Car Wash, took place in November 2016 in Rio de Janeiro, as ex-Governor Sérgio Cabral was accused by Brazilian federal prosecutors of facilitating $65.6m in bribes over infrastructure contracts for World Cup and Olympic projects. Another ex-Governor of Rio de Janeiro, Anthony Garotinho, was recently arrested on suspicion of attempted vote-rigging in last month’s municipal elections. The political and economic mood is tense in Rio de Janeiro.

Brazil Remains the Country of the (Near) Future

Despite all the doom and gloom, the country appears to be heading for recovery as investor confidence is slowly returning. The impeachment proceedings have cleared up some of the uncertainty that was hanging over the economy for some time. At Petrobras, there has been a major shakeup, with even some of the corruption money being returned ($70 million). Crude prices appear to be on the rebound, boosted by President-elect Trump’s bullish sentiment towards a spending spree and renewed hopes of an OPEC production cut.

On the long-term, Brazil has many positive aspects, including a huge reserve of commodities, a growing young, and increasingly-educated, middle class, and a wonderful genetic mix of optimistic people.

For Brazil to finally reach its full potential, the current and subsequent administrations must carry out the following crucial reforms:

- Remove regulatory constraints (red-tape) and improve business competitiveness. According to the World Bank, the country is ranked 123 out of 185 in “ease of doing business,” 175 out of 185 in “starting a business,” and 172 out of 185 in “dealing with construction permits.”

- Brazilian Sovereign ratings still remain at junk status, with a negative outlook. The interim president must implement measures to cut debt and spur economic growth so Brazil can return to investment grade.

- Come face-to-face with its massive inequality by expanding and continuing social programs of wealth transfer and job-creation, particularly in poorer states outside of the wealthier southeast.

- Reform the inefficient public health services. A healthier population translates to higher GDP growth.

I found this great podcast by The Expat Money Show – Travis Luther and Why Americans are leaving the USA

Reforming the Country’s Education System

Reform for the country’s education system should come at a priority, particularly to educate young people from disadvantaged backgrounds. This should lead to a reduction in crime rates, especially in urban areas. Currently, out of the 50 most dangerous cities in the world, 21 are in Brazil.

One such NGO program, of which I was fortunate to visit, is the Espaco Crianca Familia, in the favelas of Cantagalo and Pavão-Pavãozinho in the South Zone of Rio. It serves more than eight thousand children and teenagers. Created in 2001, the center offers sporting, educational, and cultural activities overlooking Rio’s beautiful natural landscape. Here are a few images of the center which I’m happy to share:

you have anything to add on how Brazil may reach its full potential? I look forward to your comments below.

Alexandre Rotenberg – Fine Art Travel Photographer

I hope you enjoyed reading this article: Brazil. The Country of the Future? If you have any questions, please contact our office HERE.

Here are a few articles you will love to read:

Like Our Articles?

Then make sure to check out our Bookstore... we have titles packed full of premium offshore intel. Instant Download - Print off for your private library before the government demands we take these down!