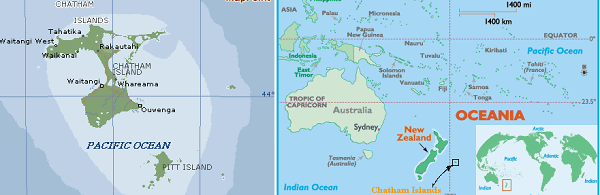

Waitangi Bay, Chatham Island. If you want an ultimate of remote and rugged isolation constantly swept by storms and the gale-force winds of the Roaring Forties, here is where you come.

And if you want to know how an unknown genocidal atrocity can teach us how to better deal with guilt-mongering, well, here too is where you come. Believe it or not, it’s in Polynesia.

This island is so old they’ve found dinosaur bones on it 90 million years old. It was part of the ancient supercontinent Gondwana, broke off from what became Antarctica, sank into the sea, subterranean volcanoes and tectonic uplift raised it back to dry land 3.6 million years ago, and remained uninhabited by man until less than a thousand years ago.

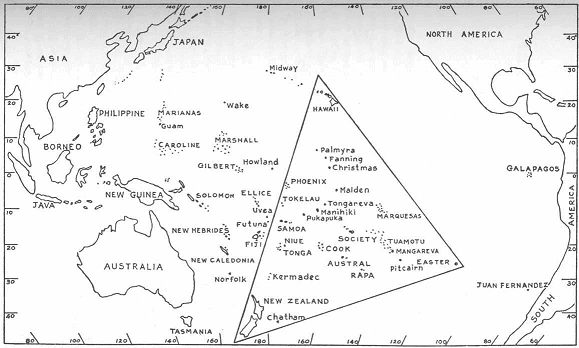

By then, Polynesians had steadily moved east across the Pacific. Originating among the aboriginal people of Taiwan, 5,000 years ago (3000 BC) they began hop-scotching down the east coasts of the Philippines, and along the north coast of New Guinea, to reach New Britain and New Ireland in about 1400 BC.

There they lingered and learned how to master the sea. By 900 BC via the Solomons and Fiji, they settled Tonga, and by 800 BC, Samoa. There they lingered again – for some sixteen centuries.

Then, starting about 700 AD, came the epic migrations by which we hail the ancient Polynesians as among the greatest seafarers of history.

Reaching the Marquesas by 700 (all dates now AD), they made those islands with the magical names (Fatu Hiva, Hiva Oa, Nuku Hiva, etc.) their cultural center, from whence they radiated out to settle Hawaii by 900, the Cooks by 1000, and Easter by 1200.

By the end of the 13th century (around 1300), a series of migrations from Rarotonga and other islands in the Cooks reached New Zealand. Calling themselves Maoris, they settled throughout both North and South Island, separating themselves into different tribes (called iwis).

One such iwi in the southeast corner of South Island decided to conduct what turned out to be the last epic Polynesian migration. Sometime in the early 1400s, they sailed 530 miles across an unknown empty sea to reach islands they named Rekohu, meaning “misty sky.” They called themselves Moriori.

The “Polynesian Triangle” was now complete, from Hawaii to Easter to New Zealand. Note Chatham (Rekohu) at the bottom extremity.

Experience the Insider community that takes your international lifestyle to the next level. Download your FREE guide

"18 Steps to Implementing Your Plan B" instantly!

The islands were colder, the seas rougher, the skies stormier than what the Moriori were used to – but there was sea life in glorious abundance: seals, fish, shellfish such as abalone, lobsters, sea birds all in countless numbers. The main island was fairly large (360 square miles) with many tracts of dense forest, large areas of marshy peat uplands, and huge lagoons. They rarely ventured inland, as they could live such a good life along the sea.

They left their Maori homeland to escape the constant wars between the various iwis or tribes. But there were fights among them too, until one day a chief named Nuhuku-Whenua decided to put an end to it. He declared it was now a moral law that there was to be no war, no fighting, and no cannibalism between them. If two men decided they had to fight, once one of them drew blood of any amount, the fight was over.

The Moriori accepted Nuhuku’s Law and internalized it as the foundation of their mana, the moral energy that gives life meaning. As a result, they became one of the most peaceful and pacifist peoples ever known.

For 400 years they lived in peace among themselves – and in utter isolation from the world. All memories of the Maoris they left behind vanished. They came to think that they were they only people in the world – indeed, the world was their island (along with a smaller island and a handful of smaller islets), and the vast empty ocean beyond.

Their isolation was broken in the year 1791, when something huge and mysterious appeared on the horizon. It was a brig of the British Royal Navy named HMS Chatham, captained by Lt. William Broughton. The Moriori thought he and the British sailors were from the Sun and called them Sun People.

Broughton’s ship had been blown off course and stumbled upon the island, which Broughton named after his ship. His report of the island’s vast numbers of seals brought sealers, and then whalers who mostly stayed offshore in their ships leaving the Moriori alone.

But in 1835, another people arrived, and brought Hell with them.

They were a group of 500 Maori cannibals determined to take Rekohu for themselves. They had heard about the island, its great abundance of food, inhabited by people who didn’t fight. Led by two chiefs, Matioro and Pomare, they hijacked a merchant ship, Rodney, and, loaded with guns, knives, and clubs, forced the British captain to sail to Chatham.

They arrived in November and informed the Moriori the island now belonged to them. If they resisted they would be killed and eaten. Those who did not resist were now their slaves.

The Moriori retreated to a sacred place and held a council. Many argued they must fight – if they did not break Nuhuku’s Law they would die. Others said the Law was not a strategy for survival, it was a moral imperative – if it was broken, the Moriori would lose their mana.

After three days of deliberating, they decided not to fight, but to offer the Maori peace and reconciliation.

When they returned to the Maori with their decision, they were instantly attacked, “killed like sheep… we fled, but they found us and killed men, women, children, and ate them.”

I am overlooking Waitangi Beach as I am writing this. It’s where one of the many massacres took place. Over 50 Morioris were captured and laid in the sand end-to-end touching each other, parent and child, with stakes driven into them and left to die. When they died, they were roasted in an oven, cooked, and eaten.

That Maoris practiced cannibalism extensively is beyond doubt. Historian Paul Moon has catalogued all the massive evidence in This Horrid Practice, starting with the eyewitness accounts by Captain James Cook in 1769 and 1773. French Captain Marion Dufresne and 26 of his crew were murdered and eaten by Maori in 1772.

By that time, of course, the Maori had been killing and eating each other for centuries. There is an island, now a beautiful private resort, off the east coast of New Zealand’s North Island, called Slipper. On a slave-raiding trip, tribes would come down the coast, stop at Slipper to capture some islanders, and break their legs so they couldn’t escape – that way the raiders would have food waiting for them on their return journey.

One of the more infamously gruesome events was the 1809 The Boyd Massacre, when Maoris slaughtered the entire number of crew and passengers aboard the ship Boyd, almost 70 Europeans, and ate them. It was, as Moon notes drily, “The largest consumption of Europeans to have occurred at any one time in Maori New Zealand, but it was not an orphan incident.”

There were about 2,000 Moriori on Rekohu when the Maoris arrived in 1835. In 1862, the survivors wrote to the British Governor of New Zealand, Sir George Grey, begging for justice and the return of their land. The letter contained a list of 1,663 names. If a name had two crosses before it, they were killed and eaten. If one cross, they died of despair due to their enslavement. Only 101 Moriori were still alive by 1862.

Grey did not reply. The British courts ignored Moriori claims. As one Maori participant in the slaughter named Rakatau was recorded saying: “We took possession (of the island) according to our customs, and we caught all the people. Not one escaped. Some ran away but these we killed too. But what of it? It was in accordance with our custom.”

The Moriori Genocide remains unknown. To this day, the Maori have not made full amends for their atrocities, and still claim ownership of most of Chatham – although some land has been returned to Moriori descendants. On the contrary, on both North and South Island of New Zealand today, Maori never stop demanding their “rights,” and condemning the British and white New Zealanders for displacing them off “their land.”

No Kiwi politician has the courage to say, “We simply acted in accordance with your custom in appropriating the land – just be thankful we neither ate nor enslaved you.”

And should any public figure make the unforgivable mistake of publicly mentioning Maori cannibalism – even in jest as Prime Minister John Key did – the howls of outrage are deafening. New Zealand’s Premier Offends Maori Tribe by Cracking Cannibal Joke was a world headline.

Whether it’s in New Zealand or anywhere else, the hypocrisy is the same – they get to guilt-monger all they want and we never get to shove it up their nose.

The very least you can say about people from the Christian West is that they have as much moral right to be proud of their achievements as any other people on earth or in history. No more guilt-mongering.

That’s the lesson of Chatham. There’s another. It was Western Christian missionaries who put an end to Maori killing, eating, and enslaving Moriori – and each other. Today on Chatham Island there is a Moriori resurgence – but without rancor. The past is past, they say, what counts is the future.

The book to read is Moriori: A People Rediscovered by New Zealand’s foremost historian, Michael King. It’s heartbreaking – and meeting people here rising above their hideous tragedy is heartwarming.

There is a very unusual beauty and peace here. It’s windy, the weather changes every 15 minutes or so – one minute it’s raining, even hailing, the next is cloudlessly sunny – and it can get cold. But it can captivate you:

Those hills are all old volcanic cones, by the way. And the people are unfailingly friendly – like Lois here, a Moriori lady whose flower-strewn garden and fruit laden orchard is always open.

She, like all Moriori, are Christians forgiving of the past. But they sure have no tolerance for guilt-mongering. Neither should we.

©2019 Jack Wheeler – republished with permission

Like Our Articles?

Then make sure to check out our Bookstore... we have titles packed full of premium offshore intel. Instant Download - Print off for your private library before the government demands we take these down!